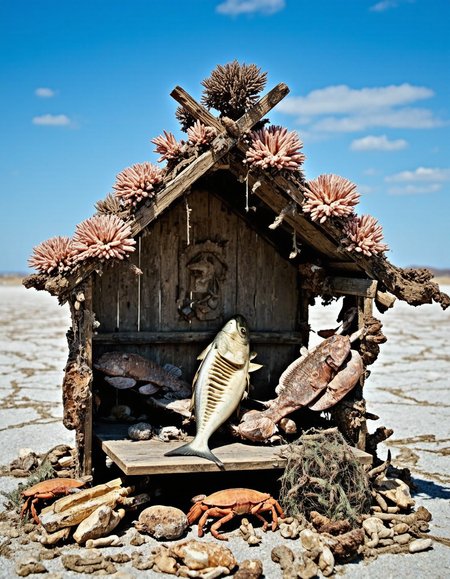

This concept imagines a world where the ocean has not just risen, but infiltrated, colonizing the dry land with all the textures, forms, and alien strangeness of the deep. Barnacles, coral, rust, and sea life erupt across inland objects and environments—coffee makers, chapels, telephone booths—overtaking them with a grotesque beauty. Yet this is no simple ecological metaphor; the growth is sentient, or at least suggestive of a will beyond comprehension. Each object becomes a shrine, each overgrown structure a conduit, transformed not by time alone, but by a slow, purposeful contamination. It’s as if some ancient, oceanic consciousness—forgotten or sleeping—has begun to stretch its reach inland, reclaiming the earth one shell, one sponge, one whisper at a time.

At the heart of the theme lies cosmic dread, echoing the spirit of Lovecraft: the notion that human civilization is fragile and insignificant before ancient, unknowable forces. The ocean becomes a stand-in for the void—teeming with life, yes, but with indifferent, alien life, unbound by logic or mercy. Its intrusion brings with it both physical decay and spiritual collapse. To encounter a coral-crusted machine or a barnacle-wrapped crucifix is to confront a timeline where humanity is no longer the dominant force, but a fossilizing memory, slowly being rewritten in sponge tissue and reefstone. These scenes are not dystopian—they are post-human. The deep has risen, and it is patient.